DiasPOURa: Palestine

Exploring the rich history, resilience, and identity of Palestinian coffee culture.

Palestinians, indigenous to the Palestine/Israel region alongside Jews, trace their lineage back to the ancient Canaanites, the region’s original inhabitants. Genetic studies confirm this shared heritage, even as centuries of religious conversions and cultural shifts have shaped Palestinian identity.

Initially practicing Judaism, many Palestinians converted to Christianity and later to Islam, all while adopting aspects of Arab culture through a process called Arabization. This transformation, however, did not alter their ethnic roots or their deep connection to the land. The Palestinian coffee culture, which evolved over centuries through Bedouin traditions and Ottoman influences, reflects this enduring heritage.

Amidst the history of colonialism, displacement, and conflict, coffee has remained a powerful symbol of hospitality, resistance, and identity, as vividly captured in the works of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. Darwish’s verses highlight the resilience of the Palestinian spirit, even as their collective memory faces systematic erasure. The story of Palestinian coffee culture, intertwined with the nation’s complex history, reflects a narrative of persistence, belonging, and a longing for freedom.

Pre-Ottoman (Pre-1516)

Coffee’s history is murky, much like the ichor itself. Before its consumption as a beverage, nomadic mountain warriors of the Galla tribe used coffee in Ethiopia, where the plant is indigenous. Initially consumed as food between 575 and 850 C.E, beans of the cherry were crushed into balls of animal fat and eaten. While some historians date coffee’s first cultivation to 575 C.E in Yemen, the bean was first described by Arabian philosopher and astronomer Abu Bakr al-Razi (Rhazes) between 850-922 C.E for its medicinal usage, then later by Ibn Sina (Avicenna).1

Coffee’s consumption as a beverage is attributed to the Sufis of Yemen, who utilized it during their nightly rituals, or dhikr. By the 15th century (1401-1500)2, the monks would craft a drink called qahwa. Originally qahwa was derived from khat — yet another plant native to Ethiopia. After the discovery of coffee, the khat was replaced by qishr, a drink made from the pulp of fermented coffee cherries.3

Historical records trace Palestinian coffee culture to the Bedouins, nomadic Arab tribes who roamed across Arabia, including Palestine. These tribes prepared their ‘qahwah sadah’ (plain coffee) by flame-roasting beans and grinding them with a mortar and pestle. The freshly ground coffee was brewed in a dallah (an Arabic coffee pot) with water and often cardamom, producing a rich, aromatic beverage.

Serving coffee is a sign of hospitality in Bedouin and other Arab cultures. Guests were typically offered one to three small cups, each partially filled. After the last cup, guests would say “daymen,” a polite gesture meaning “always,” implying, “May you always have the means to serve coffee.”

Being nomadic, the Bedouin’s had undeniably come across coffee prior to it’s spread throughout the Levant, as by 1414 the plant was known in Mecca, and was spreading to the Mameluke Sultanate of Egypt by the 1500s by way of trade and Islamic practice.

Ottoman Period (1516—1880)

After Yavuz Sultan Selim of the Ottoman Empire defeated the Mamluk ruler, Kansu Gavri in the Battle of Marj Dabiq, Syria and Palestine to joined the Ottoman lands. With their conquest—they also brought their coffee culture. Within the Ottoman Empire, coffee grew beyond its Islamic roots, no longer being solely affiliated with religious practices. Instead, it became a social venture akin to what we see in modern-day society. In addition to the Arabic dallah, the Ottomans used the cevze/ibrik to prepare coffee.

Though the first coffee houses appeared in Damascus, Ottoman coffeehouses also sprouted up in Mecca and the rest of the Arabian peninsula before finally landing in Istanbul and Baghdad. During the Ottoman occupation, the ministers of Istanbul built cafes at their own expense in the countries under their control to benefit from the rental allowances. The governor of Baghdad (Sinan Pasha), known as (Gala Zada), commissioned the architect (Proizaga) to build a cafe for him in one of the shops of Baghdad, and the cafe (Khan al-Kumark) was built in (1590 AD). This cafe is the first cafe built in the capital, Baghdad.4

Author’s Note: I did not write this following section. See footnotes for attribution.56

As much as coffee was liked and accepted by the citizens during the Ottoman Empire, it was punitively criticized by the Sultan leaders who considered it a substance causing opposition at the coffeehouses in Istanbul. Coffee drinkers were frequently known as dissident to the empire which ruled much of the Mediterranean.

By the 16th century, the commoners where the Ottoman Empire reigned had taken a liking to the beverage, and the first coffeehouses were opened in the 1550s. The coffeehouses became a place where people gathered to exchange ideas and debate freely with out fear of the Sultans. After the assassination of Osman II in 1622, his brother Murad IV became ruler from 1623 to 1640.In 1633, the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV cracked down on a practice he believed was provoking social decay and disunity in his capital of Istanbul. The risk of disorder associated with this practice were so dire, he apparently thought, that he declared transgressors should be immediately put to death. By some accounts, Murad IV stalked the streets of Istanbul in disguise, whipping out a 100-pound broadsword to decapitate whomever he found engaged in this illicit activity.

Murad IV never banned coffee wholesale. He just went after coffeehouses, and only in the capital, where a janissary uprising would pose the most risk to his rule. Murad IV kept on drinking coffee—and liquor—himself, and tolerated consumption so long as it occurred in socially homogeneous households.

The Sultan’s successors continued his policies, to greater or lesser degrees. By the mid-1650s, over a decade after Murad IV’s death, Çelebi wrote that Istanbul’s coffeehouses were still “as desolate as the heart of the ignorant.” Although by that time a first coffee drinking offense resulted in just a beating; only a second offense would get a coffee drinker sewn into a bag and thrown into the Bosporus. But coffee culture survived in the background, and popped right back under more lax or unconcerned rulers later in the century.

Post-Ottoman

Starting in 1880, over 25,000 Jews immigrated en masse from mostly Europe, to Palestine in what would be called the ‘Aliyah(s)’7. Seeking an escape from the Pogroms8 in Russia, this immigration was based on a Jewish national movement would eventually develop into the Zionist movement9. The World Zionist Organization, established by Theodor Herzl in 1897, declared that the aim of Zionism was to establish “a national home for the Jewish people secured by public law.”10

Ultimately the politics of Zionism was influenced by nationalist ideology, and by colonial ideas about Europeans’ rights to claim and settle other parts of the world. In this context, the aforementioned claim of ‘colonization’ is in-reference to the Balfour Declaration of November 2nd, 1917, in-which the government of Great Britain announced its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, to which was land that it did not own11. Furthermore, The declaration specifically stipulated that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.”

Britain wouldn’t govern Palestine until the League of Nations granted them the ‘Mandate of Palestine’ five years later, in 1922.12

It should also be noted that in July of 1915, the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence states that the Government of the United Kingdom agreed to recognize Arab independence in a large region after the war in exchange for the Sharif of Mecca launching the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire.13 Britain walked back on this promise in the Skies-Picot agreement (1916), a secret plan with the French that divided the Middle East between the two countries after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. This resulted in the creation of the British Mandate of Palestine, which existed between 1919-48.14

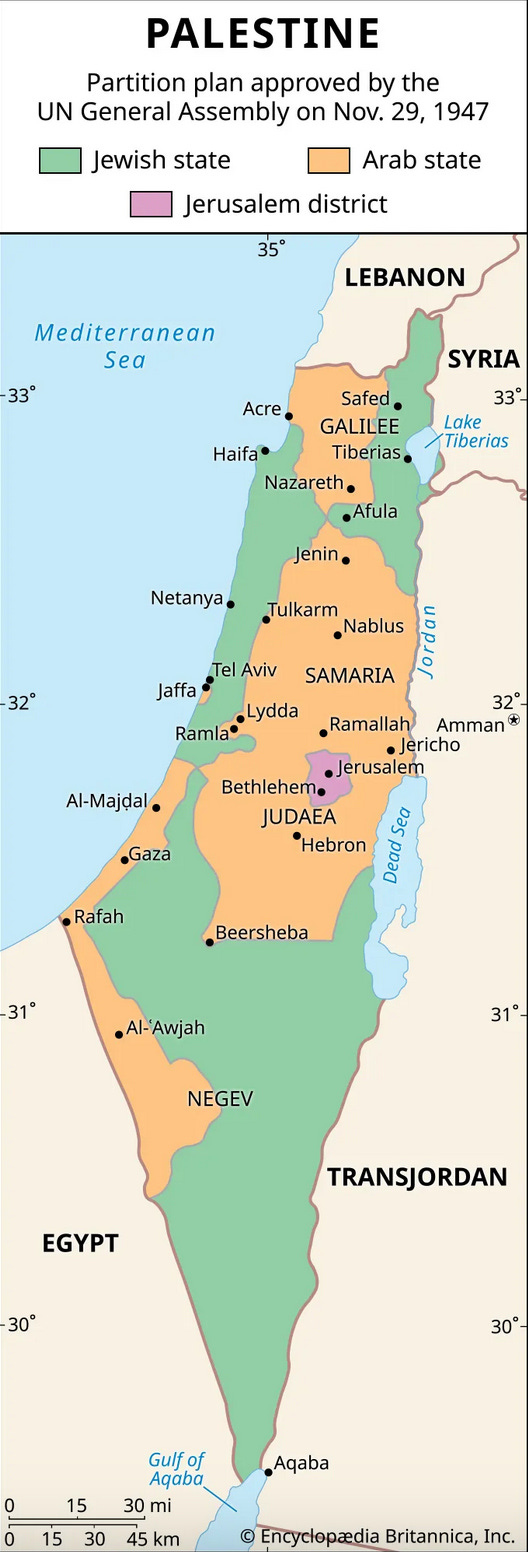

Tensions rose between Arab Palestinians and the Jewish immigrants. Between 1920-1936, a series of protests-turned riots broke out across the land. Included in this, was The Great Palestinian Revolt (Thawrat Filastin al-Kubra). All together, these conflicts led to the deaths of tens-of-thousands of Arabs, and thousands of Jews alike. These conflicts then boiled over into a civil war based off of the United Nations’ Partition Plan for Palestine, also known as Resolution 181 (II) of 1947.15

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine would be a two-state solution that would give the Arab state 42% of the territory, the Jewish state 56%, with the remaining 2% being an international zone that encompassed Jerusalem and Bethlehem.1617

As of 1944, there were roughly 1,061,277 Arabs, and 528,702 Jews, meaning 30% of the population would receive a majority of the land over the Arabs, who made up 60% of the population.18

The Jewish Agency for Palestine, later known as the Jewish Agency for Israel, accepted the partition plan, although the percentage wasn’t nearly as large as they’d hoped, as cited in a letter Ben-Gurion (head of the aforementioned executive committee of the Jewish Agency) wrote to his son:

Does the establishment of a Jewish state [in only part of Palestine] advance or retard the conversion of this country into a Jewish country? My assumption (which is why I am a fervent proponent of a state, even though it is now linked to partition) is that a Jewish state on only part of the land is not the end but the beginning.... This is because this increase in possession is of consequence not only in itself, but because through it we increase our strength, and every increase in strength helps in the possession of the land as a whole. The establishment of a state, even if only on a portion of the land, is the maximal reinforcement of our strength at the present time and a powerful boost to our historical endeavors to liberate the entire country.

[…]On the other hand there are fundamental [emphasis original] historical truths, unalterable as long as Zionism is not fully realized. These are:

1) The pressure of the Exile, which continues to push the Jews with propulsive force towards the country

2) Palestine is grossly under populated. It contains vast colonization potential which the Arabs neither need nor are qualified (because of their lack of need) to exploit. There is no Arab immigration problem. There is no Arab exile. Arabs are not persecuted. They have a homeland, and it is vast.

3) The innovative talents of the Jews (a consequence of point 1 above), their ability to make the desert bloom, to create industry, to build an economy, to develop culture, to conquer the sea and space with the help of science and pioneering endeavor.19

The Palestinian Arab leadership including the Arab Higher Committee and the Arab League, boycotted it the partition entirely—arguing that it was unjust because Arabs formed a two-thirds majority and already owned most of the land. Declaring their intent to prevent the plan's implementation, their rejection led to a civil war in Palestine as Israel declared their independence, which would then turn into the greater 1947–1949 Palestine war.

1947–1949 Palestine War and the Nakba

Amid the 1947-1949 war was the 1948 ethnic cleansing known as the Nakba, or ‘catastrophe’ in Arabic. During the Nakba, over 700,000 Palestinians were displaced, and hundreds of towns and villages were depopulated and destroyed by Israel. This mass exodus was accompanied by a systematic erasure of Palestinian identity and culture, leading to a shift in Palestinian coffee culture to an Israeli focus.

By the start of the Nakba, the coffee culture in Palestine had started to change. While Arabic and Turkish preparations methods were still prominent, the Jews that immigrated from Europe brought with them European-style brewing, which included the usage of kettles and filters.

Over the course of the war, Israel replaced over a thousand historic Palestinian place names with Hebrew names, some of which were derived from the original names, while others were completely new inventions. The destruction of non-Jewish historical sites further pushed this cultural cleansing, with over 80% of mosques being destroyed. In this destruction included several of the first cafes in the region, some of which had been around since the days of the Ottoman Empire.

For this reason, Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, utilizes the concepts of tangible memory, nostalgia, and coffee in his literary work, representing a memory of Palestinian life before the Israeli occupation. During the Nakba, Darwish's family fled their home in al-Birwa to Lebanon, but when they returned a year later, the village had been razed and replaced by two settlements. Since Darwish had not been present for the first Israeli census, he was labeled a "present absentee"—a non-citizen Arab subject to military rule.

In the 1960s, Darwish became part of a generation of resistance poets (šuʿarāʾ al-muqāwama), who broke with tradition to develop a politically committed style of Arabic poetry. His breakthrough poem, Biṭāqat huwīya (Identity Card), captured the Palestinian plight and warned the Israeli government of growing anger amidst a population under occupation.

In his poem Arba'at 'anawīn shakhsiyya - Mītr murabba' fi-l sijn (Four Personal Addresses - One Square Meter of Prison), Mahmoud Darwishn stresses a sense of longing for his native village, using the aromatics of coffee to transport himself and the reader to a world that has been lost,

“I love the particles of sky that slip through the skylight—a meter of light where horses swim.

And I love my mother's little things,

The aroma of coffee in her dress when she opens the door of day to her flocks of hens."

Amid the systematic erasure of Palestinian identity and culture following the Nakba, Darwish's use of tangible memory and nostalgia serves as an act of resistance. By drawing on symbols like coffee, he reconstructs a collective memory that connects Palestinians to their heritage and the lives they once knew.

"I did not yet know my mother's way of life, nor her family's,

When the ships came in from the sea.

I knew the scent of tobacco in my grandfather's aba,

And ever since I was born here, all at once, like a domestic animal,

I knew the eternal smell of coffee."

—Qarawiyyün, min ghayr su (The Kindhearted Villagers),

What is Collective Memory?

Collective memory refers to the shared memories, knowledge, and traditions within a social group that significantly shape its identity. It encompasses the profound stories of past events, such as the Nakba, the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and The Holocaust, as well as daily cultural practices, like a ritual of coffee preparation. More than just historical remnants, these shared memories influence the group’s present perspectives and future aspirations.

In Palestinian culture, collective memory is a vital link to experiences of displacement, resistance, and resilience. Stories, rituals, and symbols such as the keffiyeh in the Palestinian culture continuously nourish collective memory, playing a role in building community and sustaining cultural identity.

In Memory for Forgetfulness, Mahmoud Darwish recounts the relentless bombing during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon. The sea, filled with an enemy fleet, transforms into "one of the fountainheads of hell." Despite the devastation around him, Darwish expresses a compelling need to reach the kitchen and make his coffee. A glass partition separates the bedroom from the kitchen, which is exposed to fire from bombers and snipers. Every time he wants to make coffee, he has to account for the risk to his life.

“I want the aroma of coffee. I need five minutes. I want a five-minute truce for the sake of coffee. I have no personal wish other than to make a cup of coffee. With this madness, I define my task and my aim. All my senses are on their mark, ready at the call to propel my thirst in the direction of the one and only goal: coffee. Coffee, for an addict like me, is the key to the day.”

In Memory for Forgetfulness, Darwish conveys an almost manic desire for his cup of coffee, even if it means putting his life at risk. Coffee is no longer just a gateway to the collective memory of pre-colonized Palestine; it also embodies hope, nationalism, and liberation under occupation.

If you’re gonna debate in my DMs or comment section, please start your sentence off with ‘Pumpkin’ so I know you read the entirety of the article. Normal readers, please ignore this sentence and continue! :^)

Coffee has long been exploited as a commodity under colonial rule. Baristas are underpaid and mistreated, while coffee producers suffer even more. Although coffee is synonymous with liberation, it is also intertwined with the suffering endured during the fight for freedom. At what cost should Israel exist? How much suffering, bloodshed, and generational trauma must the Levant inherit by its native peoples?

The unjust treatment of the Palestinians has become a collective memory of the subjugated and the oppressed—one that isn’t going anyway anytime soon.

Free Palestine.

Footnotes/Glossary: Please take the time to read Ayesha Kuwari’s work on the subject, to which much the latter half of this article was inspired by.

The sources are all live. Currently finding a way to source all of them consistently..

The African word for the coffee plant is bun, which then became the Arabica bun, meaning both the plant and the berry. Rhazes (850-922 AD) , a doctor who lived in Persian Iraq, compiled a medical encyclopedia in which he refers to the coffee bean as bunchum. His discussion of its healing properties led to the belief that coffee was known as a medicine over a thousand years ago. Similar references appear in the writings of Avicenna (980-1037 AD) , another distinguished Muslim physician and philosopher. When used in reference to the beverage, the word ‘coffee’ is a modified form of the Turkish word Kahveh, which is derived from the Arabic word, Kahwa, which means ‘wine.’ This word derivation reflects the belief that coffee has an effect on people that is similar to the intoxication caused by alcohol.Coffee was also used to treat an astounding variety of ailments,including kidney stones, gout, smallpox, measles, and coughs, You, D. C., Kim, Y. S., Ha, A. W., Lee, Y. N., Kim, S. M., Kim, C. H., Lee, S. H., Choi, D., & Lee, J. M. (2011). Possible health effects of caffeinated coffee consumption on Alzheimer's disease and cardiovascular disease. Toxicological research, 27(1), 7–10. https://doi.org/10.5487/TR.2011.27.1.007

Sufism is a mystic body Islamic tradition that seeks direct, personal connection with the divine through spiritual practices and a focus on inner purification.

https://books.google.com/books?id=TUo981rkwkoC

https://web.archive.org/web/20180810205940/http://www.altaakhipress.com/viewart.php?art=64196

https://coffeegeography.com/2023/01/11/coffee-drinking-punishable-to-death-during-the-ottoman-empire-in-1600s/

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/was-coffee-ever-illegal

Pogroms: Organized killing of large numbers of people, because of their race or religion (originally the killing of Jews.)

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7766/

https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/829707?ln=en&v=pdf https://time.com/3445003/mandatory-palestine/

https://books.google.com/books?id=878vAQAAIAAJ

https://books.google.com/books?id=sY27UmuT6-4C&pg=PA84

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Husayn-McMahon-correspondence

https://www1.udel.edu/History-old/figal/Hist104/assets/pdf/readings/13mcmahonhussein.pdf

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/britain-and-france-conclude-sykes-picot-agreement

https://www.britannica.com/event/Sykes-Picot-Agreement

https://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/2016/sykes-picot-100-years-middle-east-map/index.html

Historical Context: In 1947, after The Holocaust and after World War 2; The British Government wished to terminate the mandate—which led to Resolution 181 (II).

Official Resolution: https://documents.un.org/doc/resolution/gen/nr0/038/88/pdf/nr003888.pdf?token=agZk2G8Kd5tydjWtwq&fe=true

Sources for land division:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/United-Nations-Resolution-181

https://www.thecairoreview.com/essays/framing-the-partition-plan-for-palestine/

https://www.un.org/unispal/history/

Historical Context: In 1947, after The Holocaust and after World War 2; The British Government wished to terminate the mandate. They then let the [newly established] United Nations handle the resolution of Palestine, which then led to the creation of Resolution 181 (II).

Paragraph sourced from (In collaboration with): https://www.kafekuwari.com/blog/coffee-as-memory-the-palestinian-struggle-mwl9j

Population:

Israeli Source:

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jewish-and-non-jewish-population-of-israel-palestine-1517-present

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/population-of-israel-palestine-1553-present

Palestinian Source: https://assets.nationbuilder.com/cjpme/pages/2116/attachments/original/1655220704/07-En-Demographics-Factsheet_v02.pdf?1655220704