You Will Own Nothing: The Illusion of Digital Ownership

Exploring the Temporary Nature of Purchased Media in the Metamodern.

Intro.

memeχ dictates that as media evolves, so do methods of consumption. From Limewire to Spotify, the digital age has transformed how we access, discover, and experience media. Bungie’s management of Destiny 2, a Massively Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Game (MMORPG), will serve as a prime example, along with Kanye West’s "Life of Pablo" and Childish Gambino’s "3.15.20”.

Both albums experienced post-release updates that altered or removed original content. Similarly, Bungie’s approach to Destiny 2 content management raised controversy about digital rights management (DRM) in video games, as players lost access to content they’d paid for.

With streaming, we sacrificed ownership and the physical experience for convenience and accessibility. In this article, we will explore the nuances of these sacrifices by examining instances where digital content was altered or removed entirely.

Destiny 2’s Content Vault:

Destiny 2 is an online multiplayer first-person shooter developed by Bungie. Released in 2017, the game has expanded significantly over the years with multiple downloadable content (DLC) expansions.

In June 2020, Bungie announced a significant change in how they would be managing Destiny 2’s growing content. Bungie explained that Destiny 2 had become “too large to update and maintain efficiently.”1 The game required players to download up to 115GB of worth of data to access all of the available content. With around 25GB of new content added each year, the game became increasingly harder for developers to patch and continued to take up more space on users’ hard drives.

To address this issue they introduced the Destiny Content Vault (DCV). The DCV aimed to cycle older, less-played content out of the game to make room for newer content. While this allowed Bungie to innovate and respond to player feedback more rapidly, it also meant that players lost access to content they had previously paid for.

Bungie explained that this approach was necessary to keep the game manageable. To further their decision, they pointed out the statistics regarding the inefficiency of the available content that Destiny 2 had accumulated.

“Warmind’s campaign represented only 0.3% of all time played in Season of the Worthy, yet the Warmind Expansion accounts for 5% of our total install size. This dramatic imbalance between player engagement and overall maintenance cost is found in much of our legacy content.” — Bungie

While Bungie stated removing ‘legacy’ content was necessary for the game’s long-term health, many players felt lost and frustrated at being unable to access the content they’d paid for. Legally, Bungie was well within in their legal right. As a consumer we pay for a license to access the content—a license that Bungie has the right to revoke at any given moment.

This concept of ‘vaulted’ content isn’t isolated to the video game industry. Despite the narrative being framed as a necessity for maintaining a viable game, the removal of content is one of the many complexities of digital rights management (DRM) across several industries.

Kanye West: Life of Pablo

In February 2016, Kanye West released his seventh studio album, "The Life of Pablo." Upon release, Ye tweeted that the album was a “living, breathing, changing creative expression.” Following its initial release, the album underwent numerous updates and changes, with tracks being added, removed, or altered over several months.

These ongoing changes were unprecedented in the music industry and illustrated the potential of artists utilizing digital platforms for continuous creative modifications, similar to changelogs seen in coding projects or developer blogs in games like Destiny 2 and League of Legends.

The changes to "The Life of Pablo" were extensive. For example, the track "Wolves" was significantly reworked, with Vic Mensa and Sia being reinstated, and Frank Ocean's part was spun off into a separate track called "Frank's Track". Other tracks, like "Famous" and "Fade," saw lyrical adjustments and production tweaks to refine their sound. "Saint Pablo" was added as a new outro, further evolving the album months after its initial release.2

For fans, this meant that the version of “The Life of Pablo“ they first heard was not necessarily the same version they might listen to months later. While some welcomed this ‘ongoing development’ approach and the insight it provided into West’s creative process, others found the inconsistency of the listening experience frustrating.

Childish Gambino: 3.15.20 and Atavista

On March 22, 2020, Donald Glover, a.k.a Childish Gambino, released the album "3.15.20." The title reflected the date it premiered on DonaldGloverPresents.com, serving as a memorable zeitgeist3 for the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdowns.

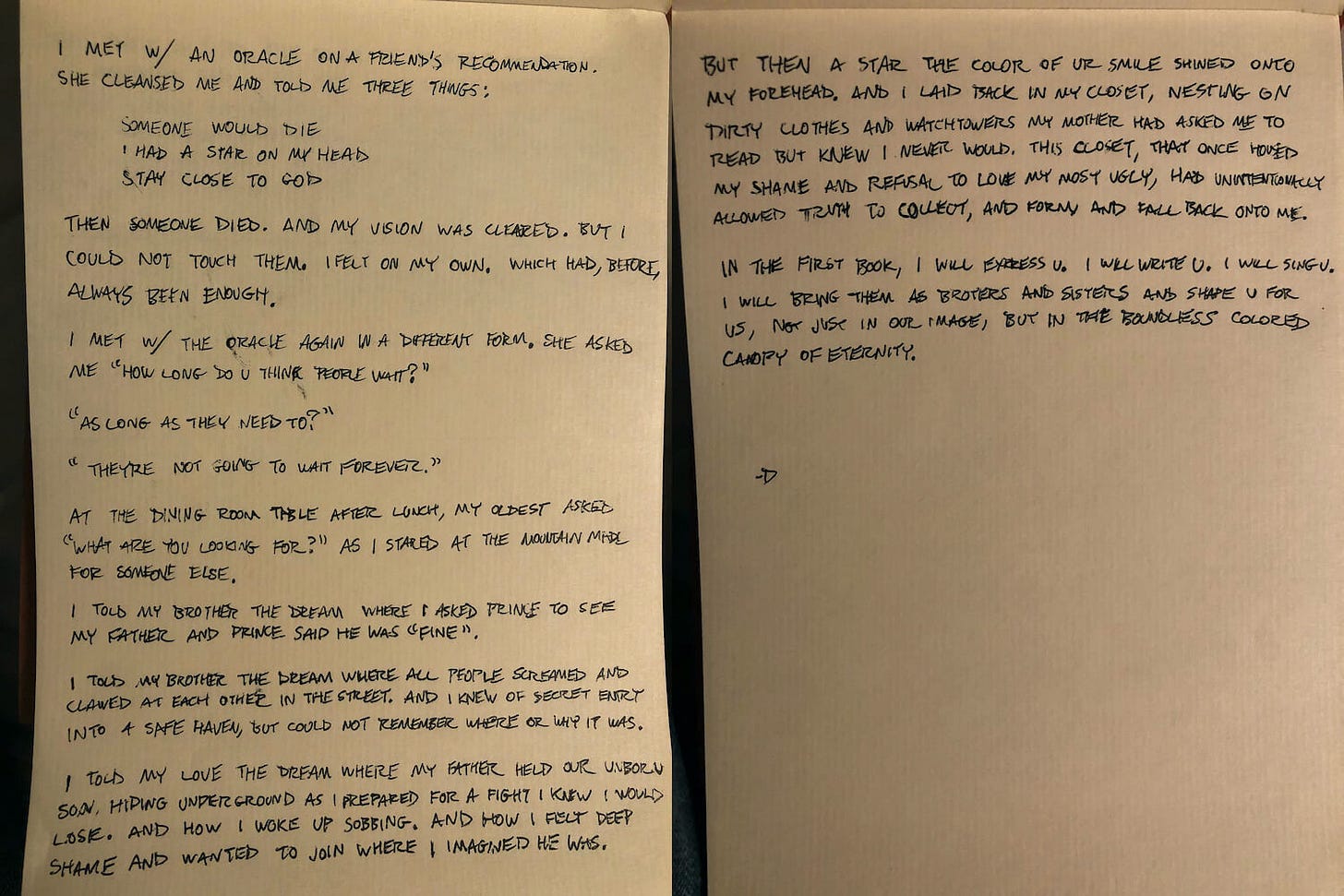

The album was available in two forms on all digital streaming platforms: a continuous play version under "Donald Glover Presents" and a standard track-by-track version under "Childish Gambino." Upon its release, “3.15.20” received mixed reviews. While praised for its musical components and Gambino’s creative expression, some found it inaccessible because of the lack of identifiable track names. Only two tracks had official titles, “Algorhythm” and “Time.” The rest were titled with timestamps indicating their starting points in the album. For instance, “12.38” began twelve minutes and thirty-eight seconds into the album. Along with the album's release, promotional artwork and a handwritten note by Donald were included, the latter of which, is available below.

Four years later, on May 13, 2024, Glover released his latest album, "Atavista.” Described as a ‘finished’ version of "3.15.20," “Atavista” included noticeable differences: several tracks were removed, two new tracks were added, and existing songs were sonically enhanced. However, the release of “Atavista” led to the removal of “3.15.20” from most streaming services, making the original tracks inaccessible.

For many fans, "3.15.20" represented more than just an album. It was a zeitgeist of the pandemic, capturing imperfection amidst the chaos of a world with an uncertain future. For some, the removal of “3.15.20” wasn’t just disappointing; it was a loss of something personal and irreplaceable. One fan expressed their frustration, stating:

“I have a lot of respect for artists' wishes for their work so I understand why Donald would want to remove it. However, I don't like the fact that when he removed it we lost something. If Atavista was just 3.15.20 plus some songs then I wouldn't mind so much, but shock is gone now and so are all the sweet transitions on the original album. I'm disappointed that this is the route he went but it's his work so he gets to do what he wants even if we disagree. That album will always be very special to me, so the fact that it's just gone is incredibly frustrating. But it's whatever, that's why God created local files 🙏” — Mismo

Another fan noted the inconsistency across streaming platforms:

"I think it's kinda cheese that Tidal and YouTube still have the DGP version, and Spotify doesn't."— Djmakproto

One of the most insightful claims was from /u/rocker2014 on Reddit:

Streaming is convenient, cheap, and has become the norm in modern culture. But you don't own anything you stream. Just like Donald did with this album, any artist can remove their music at any moment. You kind of consent to this by not actually owning any of it.

I bought 3.15.20 on iTunes when it came out. So I can now listen to both 3.15.20 and Atavista whenever I want. I have it uploaded into my YouTube Music app so I can stream it and have the digital copies on a hard drive so I'll never lose them.

And not only that, but artists get very little money from streaming. They get much more from you buying their music.

Even though it seems antiquated, buying music is the better way to support artists and retain ownership of the music you purchase. Buy the vinyl, buy the CD, the digital download, the cassette, whatever your preferred format is. Support the artist and own the music.

Digital Ownership in Streaming

Purchasing media used to imply that we owned it outright. While you were legally bound not to reproduce or share the work with others, it was still yours to keep and manipulate as you saw fit. However, with the rise of digital platforms, the concept of ownership has changed.

When we subscribe to streaming services and register with digital stores like Steam, the App Store, Epic Games, or Google Play, we access vast libraries of content—some of which we can purchase and some of which we can download or stream for free. The caveat to these digital platforms is that we own nothing. Even ‘purchased’ items are merely licenses to access said digital content.

Music streaming platforms operate similarly. Although they’ve revolutionized how we consume music, they’ve also shifted ownership from physical media to digital access. Streaming merely grants temporary rights to content hosted by the service. Even when media is downloaded for offline listening, they remain tied to the streaming service through DRM. Furthermore, this content can be changed, removed, or added as seen with Kanye West’s “The Life of Pablo” and Childish Gambino’s “3.15.20.”

For this reason, physical copies of media such as CDs, vinyl records, and video games are resurgent. Physical media provides users with complete control over their library. Even digital ‘purchases’ from platforms like iTunes are only partially safe. Apple allows providers to offer and remove items from the store at their discretion, meaning you can only re-download your purchases if they are available in the store. Once the provider has removed it, not even Apple can provide it again.

In the case of the PlayStation Store, “P.T.,” a highly acclaimed demo developed by Hideo Kojima and Guillermo del Toro, was removed. After its removal, users who had downloaded it could not re-download the demo, leading to PlayStation consoles with “P.T.” installed being sold at a premium on websites such as Ebay and Facebook Marketplace.

As we delve into the implications of digital ownership, it’s crucial to consider the balance between experience and convenience, which will be the focus of the next article. The implications of streaming go far beyond being ‘well-informed’ about our relationship with digital media—as streaming affects artists just as much [if not more] than consumers.

https://www.bungie.net/7/en/News/article/49189

https://www.xxlmag.com/kanye-west-the-life-of-pablo-changes/

Zeitgeist: The defining spirit or mood of a particular period of history as shown by the ideas and beliefs of the time.