i. Defining meme_x

Media, Evolution, and Metamodern Experiences

Media

Evolution

Metamodernism

E(χ)periences

The media landscape is oversaturated, and algorithms have run rampant, immobilizing society’s ability to think critically—and find information that exists outside ones own native-internet experience.

It’s for this reason, that we need a new way to understand, navigate, and disseminate our relationship to—and with media, both physically and digitally.

memeχ is a metamodern framework, or a "way of thinking" for media analysis and creation. memeχ proposes that culture evolves through oscillations—predictable, cyclical shifts between opposing values, such as sincerity and irony, or analog and digital. By understanding these oscillations, creators can not only predict the future—but develop media that will reach audiences in a more intentional way.

The name memeχ honors Vannevar Bush's memex—a visionary device for organizing and accessing that was explored in his essay, As We May Think (1945). Instead of a hypothetical machine, memeχ builds on the mythological device in Bush’s essay. By developing memeχ into a framework for the human experience, we can adress present and future challenges in contemporry media, including; algorithms, misinformation, deepfakes, and oversaturation of media.

First, we will exlore the foundations of memeχ through its philsophical background in metamodernism—then we will breakdown oscillations to understand the ebb-and-flow of how culture navigates ideas, thoughts, and feelings. Finally, we will provide examples of the memeχ and how it can be (and is) applied to modern-media creation and consumption.

This section provides the philsophical context and general foundation(s) for metamodernism, to which, memeχ is the application of this philosophy [metamodernism].

ii. The Philosophy of Modernism, Postmodernism, Metamodernism

Modernism

Modernism emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a reaction to the changes brought about by industrialization, urbanization, and the First World War. Modernism is represented by the will to break from tradition and discover new forms of expression that were capable of capturing the reality at the time.

Modernists embodied a belief in progress, innovation, and the power of human creativity to reshape society and reveal universal truths through art.

Key Characteristics of Modernism:

Innovation

A push for new techniques and styles in art, literature, and music.

Examples: Stream-of-consciousness narration in literature (e.g., James Joyce) and atonality in music (e.g., Schoenberg).

Exploration of Form

A focus on the structure and medium of art itself, often resulting in abstraction and experimentation.

Example: Cubism in painting (e.g., Picasso) challenged traditional representations of reality.

The Hero’s Journey for Authenticity

A desire to uncover the essence of human experience, free from outdated conventions or constraints.

Modernists believed art could reveal universal truths about life, identity, and society.

Postmodernism

Postmodernism arose in the mid-to-late 20th century, largely in response to Modernism's perceived limitations and failures, especially in light of the horrors of World War II, which shattered Modernism’s progress in universal truths.

Postmodernists approached the world with skepticism and irony, rejecting the idea that art or philosophy could uncover a singular, objective truth. Instead, they embraced plurality, ambiguity, and relativism, viewing reality as socially constructed and inherently fragmented.

Key Characteristics of Postmodernism:

Skepticism and Irony

A critical stance toward objective knowledge, grand narratives, and cultural ideologies.

Example: Postmodern literature often questions reality and meaning (e.g., Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five).

Pastiche and Parody

The blending of styles, genres, and media to expose the artificiality of “reality.”

Example: Postmodern architecture mixes classical and modern designs without concern for coherence.

Rejection of Grand Narratives

A dismissal of overarching stories that attempt to explain history, culture, or the human condition.

Example: Instead of one universal truth, Postmodernism embraces multiple perspectives and interpretations.

While Modernism sought meaning and order, Postmodernism revealed the chaos, subjectivity, and contradictions of life in a fragmented world.

Metamodernism

Metamodernism, emerging in the early 21st century, can be understood as a response to Postmodernism’s skepticism and detachment. While it acknowledges the failures of grand narratives and the ambiguity of truth, Metamodernism also recognizes humanity’s renewed desire for meaning, depth, and sincerity in an increasingly complex and digital world.

Metamodernism does not reject irony or skepticism—it embraces them. However, it also allows space for hope, authenticity, and idealism to coexist. Metamodernism does not seek to find balance, but instead chooses to oscillate between the extremes of modernism and postmodernism—truth and ambiguity, irony and sincerity, optimism and despair.

Key Characteristics of Metamodernism:

Synthesis of Opposites

A movement between Modernist idealism and Postmodernist skepticism.

Example: Art and culture oscillating between irony and sincerity, without settling on either.

Informed Naivety and Pragmatic Idealism

A willingness to hope and dream, while fully aware of the limitations of past ideologies.

Metamodernism reflects a pragmatic optimism—striving for new possibilities while understanding their imperfections.

Dynamic Engagement

Instead of fixed viewpoints, Metamodernism encourages continuous growth and engagement with the world.

Example: The blending of nostalgia and innovation in media (e.g., the resurgence of vinyl records alongside streaming)

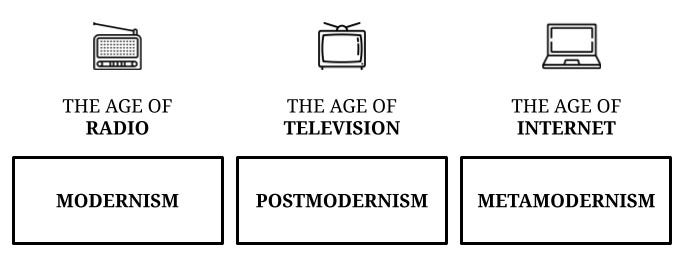

From Modernism to Metamodernism

To understand Metamodernism, it helps to view it [Metamodernism] as a reaction and reconciliation through time:

Modernism sought universal truths through innovation and creativity.

Postmodernism shattered those ideals, revealing a fractured, pluralistic reality.

Metamodernism oscillates between these perspectives, striving to create meaning of the ‘in-betweenness’ while embracing complexity and contradiction.

Metamodern is not the end-point, instead it’s the journey between two destinations. Between point A and B, there are an infinite amount of stops, and such is metamodernism. It reflects, and measures the way humanity navigates the pendulum swing of progress and reaction—swaying between hope and doubt, tradition and innovtion, and old and new.

iii. Oscillations

The Concept

An oscillation is the movement between two points, in physics this is observed through a pendulum swinging between two extremes. The human experience is no different. Just as a pendulum swings between two extremes—so too does culture, technology, and human behavior. These cycles are often recurring, and are always predictable, as they’re the driving force of cultural evolution.

In the frame of meme_x, an oscillation is a cyclical shift in collective values and behaviors between two opposing thought-forms. These thought-forms can be physical/technological (analog vs. digital), philosophical (sincerity vs. irony), or social (community vs. individualism). It’s through identifying, and understanding why these trends emerge, that we can predict the future to understand the fundamental [media] needs of what will come.

Generations and Media: Inherited Processes

Each generation builds on its predecessor, creating a lineage of media engagement that feels almost like an inherited family trait. However, this inheritance is not passive—new generations react, reforge, and reinterpret what they receive, forming an oscilltion between the future they’re born into and the past that molded them.

Example: Growing up in the 90s/2000s might’ve meant you experienced a hybrid of portable CD players, digital music stores, and eventual smartphone streaming. Now, there’s a return to vinyl records—an oscillation between nostalgia for tangible, physical media and the convenience of digital platforms.

Vinyl presented not just a return to nostalgia but also a return to physicality and ownership, with record-digging being its own human-powered algorithm of sorts. In addition, vinyl curated its own community, and exclusivity. Vinyl (much like CDs) offered album art, producer credits, and a series of extras that are lost on digital streaming platforms.

The Pattern Repeats Itself

This same oscillating pattern appears across our culture, revealing a collective negotiation with technology and meaning:

Photography: The revival of film cameras and the popularity of apps that create grainy, "imperfect" digital polaroids represent an oscillation between the sterile perfection of smartphone cameras and a desire for authentic, unpredictable aesthetics.

Reading Culture: The explosive growth of #BookTok and the renewed focus on libraries showcases an oscillation between the isolating, algorithm-fed nature of social media and a sincere, community-driven celebration of physical books and shared-community within third-spaces.

Digital Ownership: Even th rise of NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) can be understood as an oscillation. It not only brings out the idea of a sacred, provable ownership and scarcity, but leans into the early internet-days of Neopets and forum-signature pets. From the physical world, it drawns upon collectibles and TCGs (Trading Card Games).

Conclusion

By observing to become aware of these cultural pendulums, we move ourselves from being passive subjects of media trends to becoming intentional creators and consumers that understand the forces that shape our experience.

Most oscillations, can be understood as an inheritance of the past, trying to maintain, and uphold its relevancy in the present. What may be obsolete to one generation might just be essential to the next. And what was groundbreaking, may too become limiting, especially as new technology inform how we interact with media.

iv. meme_χ for dummies: a framework for creation

While memeχ can be used to analyze culture, it’s really a practical guide for creating media that resonates with audiences. Therefore, one must navigate the most critical oscillation there is: the oscillation between the creator and the consumer.

On one end, you have the Modernist Auteur—the visionary with a top-down, finished product that is uniquely theirs, delivered to a mostly passive audience. The end-product is all about the Auteur’s singular vision. Even if the audience was taken into consideration whilst being crafted, they had no hand in its construction.

The other extreme is the Postmodern Participant, where the lines between Creator, Product, and Audience are all but erased. The audience is no longer passive. Instead, it acts as a fourth-wall breaking force that reinterperets, remixes, and collaborates with the Creator and Product alike, until they [the audience] become co-creators. (Think TikTok Trends, and Twitch/Youtube Culture, specifically Mr. Beast).

This dynamic mirrors a famous concept in quantum physics: the double-slit experiment. The very act of observing [read: measuring] a particle changes its behavior; similarly, the audience's active participation fundamentally affects the art's final meaning and trajectory.

Gone is the age of the celebrity. Now is the age of the influencer/content creator. The difference between the celebrity and the influencer is that the influencer/creator today, quite literally, cannot afford to live at either extreme (Auteur, or Participant). Thus, we come to understand that meaningful art requires a tactful, purposeful sway between the Auteur’s Vision and the Audience’s Engagement1.

David Ogilvy knew this decades ago, as some of his greatest advice came not from the perspective of marketing, but empathy: “The consumer isn’t a moron; she is your wife.”

This is a call for the creator to build a responsive relationship with their audience—to oscillate between their world and their audience's, because they exist in a shared one.

The Tastemaker, Curator, and The Experience Designer

So, how does a creative cultivate an experience that exists in this shared reality?

By adopting the mindset of a User Experience (UI/UX) Designer.

Most internet-based platforms obsess over a user’s needs and emotional responses. To understand their users, and how they interact with their platform, companies hire UI/UX designers. The goal of UI/UX is not to design an app that works ‘functionally’, but instead design an experience that is intuitive and purposeful for the intended audience. Those developing content under the context of memeχ do the same, but with culture, making them the tastemakers of culture.

Early on, we must understand that iterative development is part of the process. We must fail hard, and fail fast in our endeavors, throwing wet paper towels at a wall until one—or several, stick. This process however, isn’t to be confused with careless content creation. Instead, it’s the artist’s form of rapid prototyping. A postmodern acceptance of trial and error—failing hard, and failing fast. We can conceptualize ideas all we want, but until we put oru ideas practice, all we’re doing is thinking… About thinking.

It’s very rare that our ideas actually match what’s in our mind, and the faster we fail and the harder we fail, the faster we can learn and catch up to the vision that we have, even if that vision is technically unattainable (because in our head, the vision is ‘perfect’).

This experimental approach requires a mindset that overcomes the paralysis of perfectionism. As producer Kenny Beats advises, you sometimes have to D.O.T.S. (Don’t Over Think Shit). This mindset, although easier said than done, prioritizse action over analysis and momentum over perfection. In Silicon Valley terms, this is what one would call a "Minimum Viable Product" (MVP), with the goal to get ideas out into the shared reality where they can be tested, refined, or abandoned based on real-world feedback.

Ultimately, creating within memeχ means embracing this process:

Holding a sincere, authentic vision (the Modernist Auteur).

Designing an experience with deep empathy for the audience’s perspective and participation (the Postmodern Participant).

Using iterative, human-centered methods to bridge the two (the UX Mindset).

As technology such as generative AI enter our studios and writer's rooms, this adaptive and oscillatory approach—one that blends a unique vision with a profound respect for the human experience—will become more crucial than ever for creating work that stands out as not only clever, but alive.

v. Vannevar Bush and the memex

Development

memeχ took shape during my second year at Georgia State University (GSU) as a project for a Media, Society, and Culture course. Initially focused on media consumption and cultural implications, it evolved into a system for analyzing and creating media from a metamodern standpoint. This approach draws inspiration from giants like internet mentor Camden Ostrander (contributor to the Dissect podcast), whose work in media analysis showed how culture, philosophy, and technology intersect.

Vannevar Bush’s Influence

In July of 1945, weeks before the atomic bombs “Fat Man” and “Little Boy” were dropped, American physicist Vannevar Bush published “As We May Think” in The Atlantic. Bush—an academic leader, vice president and dean at MIT, president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and director of the National Defense Research Committee [NDRC]/Office of Scientific Research and Development [OSRD]—was deeply involved in WWII’s scientific efforts, including the early stages of the Manhattan Project.

During World War II, the OSRD, under Bush’s leadership, oversaw the development of technologies that played a decisive role in the war effort, including radar and sonar. However, the OSRD’s most infamous contribution was its early role in laying the groundwork for the Manhattan Project—the top-secret operation that produced the world’s first nuclear weapons.

By the end of the war, Bush stood at a crossroads. He had led science to its most destructive achievement in history, yet he believed deeply that science should serve humanity—not destroy it. In “As We May Think,” Bush reflected on this shift in priorities, urging scientists to move beyond war and turn their efforts toward progress and innovation:

“What are the scientists to do next? ... It is the physicists who have been thrown most violently off stride, who have left academic pursuits for the making of strange destructive gadgets... Now, as peace approaches, one asks where they will find objectives worthy of their best.”

Information Overload

While Bush was concerned with the role of scientists, he also identified a growing challenge: the human experience could not match the overwhelming amount of information being produced. Even in 1945—long before the internet, Bush observed that humanity was creating more knowledge than it could process, organize, or effectively use:

“The summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze... is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships.”

In other words, the tools for managing information were not keeping up with the rate at which new knowledge was being created. Sound familiar? Bush’s observation in 1945 is no different than the issue that plagues us today:

Content Overload: At this very moment, over 272 TikToks are posted per second, alongside countless articles, tweets, videos, and posts. No human being can consume or make sense of it all.

Echo Chambers: Modern algorithms curate content for us, tailoring what we see to our preferences. While convenient, this often isolates us in digital echo chambers, limiting exposure to diverse perspectives.

Despite advancements like indexed search engines and AI, we’re still struggling with the same core problem Bush described nearly 80 years ago. It’s humanly impossible to engage with even a fraction of the content thats being created, even within a specific niche. This experience of threading through a consequent maze is consistent throughout the development of technology, which makes me wonder—how much have we really changed?

As described earlier, our interaction with technology is a penedulum; one that swings with increasing velocity until its course corrected; either by time, or by the introduction of a technology that changes our perspective on how we understand all other technology. Examples of this include the computers, the internet, artificial intelligence, and the memex.

The Memex

(Summary below)

Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and, to coin one at random, “memex” will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.

It consists of a desk, and while it can presumably be operated from a distance, it is primarily the piece of furniture at which he works. On the top are slanting translucent screens, on which material can be projected for convenient reading. There is a keyboard, and sets of buttons and levers. Otherwise it looks like an ordinary desk.

In one end is the stored material. The matter of bulk is well taken care of by improved microfilm. Only a small part of the interior of the memex is devoted to storage, the rest to mechanism. Yet if the user inserted 5000 pages of material a day it would take him hundreds of years to fill the repository, so he can be profligate and enter material freely.

Most of the memex contents are purchased on microfilm ready for insertion. Books of all sorts, pictures, current periodicals, newspapers, are thus obtained and dropped into place. Business correspondence takes the same path. And there is provision for direct entry. On the top of the memex is a transparent platen. On this are placed longhand notes, photographs, memoranda, all sorts of things. When one is in place, the depression of a lever causes it to be photographed onto the next blank space in a section of the memex film, dry photography being employed. —Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think”

The slightly-less-longer TL;DR:

In "As We May Think," Vannevar Bush introduced the idea of the memex, a device imagined as a mechanized private library and file system. The memex was designed to solve the problem of information overload by allowing individuals to store, retrieve, and organize knowledge in a way that mimicked our own brain’s associative processes.

Bush described the memex as follows:

Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library... A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.

How the Memex Would Work

The memex resembled a desk outfitted with advanced technology for its time:

Slanted translucent screens for displaying information.

A keyboard, buttons, and levers to navigate and organize content.

Microfilm-based storage, capable of holding vast amounts of data without running out of space.

Users could add information in various ways:

Purchasing microfilm content, such as books, newspapers, and correspondence, for direct insertion.

Creating new entries by photographing handwritten notes, photos, or documents onto blank microfilm using a lever.

The most revolutionary feature of the memex was its ability to create associative trails. Much like how our brains form connections between memories, the memex allowed users to link related pieces of information. These trails could then be revisited, shared, or expanded upon, transforming static data into dynamic, meaningful networks of knowledge.

Why the Memex Matters Today

Bush’s vision for the memex was revolutionary not just for its time but for what it anticipated:

The hyperlink: Associative trails are the foundation of how we navigate the internet today.

Cloud storage and digital libraries: Systems that allow us to store and access vast amounts of information.

AI-driven recommendations: Tools that attempt to curate content, though often imperfectly, to help us manage the overwhelming flow of information.

While the memex was never built, its spirit—the urgent need it was meant to address—is more relevant than ever.

Thus, memeχ is the metamodern answer to Bush's postmodern challenge. It proposes that the most powerful associative trails are not mechanical, or algorithmic, but human-centric. Where technology alone cannot solve our problems, I believe human-centric computer design will advance us further as a species.

Naturally, new innovations create new opportunities and new challenges, further complicating the maze Vannevar Bush mentioned. memeχ offers a compass for that journey—a way to create with purpose, to consume with awareness, and to find clarity within chaos.

It is with memeχ, that I hope to aid in developing systems that improve understanding nd connection across the human race; rather than further obfuscating our fragile cultural borders.

Which is why J.J. Abram’s LOST is one of the greatest series of all times. It created a ‘moment’ in time that cannot be easily replicated.